For three years, the Kremlin has been financing its invasion of Ukraine by draining its coffers and relying on its oil, gas, and coal revenues. But this strategy is reaching its limits: Western sanctions cap the price of Russian crude oil at $47.60 per barrel, forcing Moscow to sell its production at knockdown prices to China, India, and Turkey.

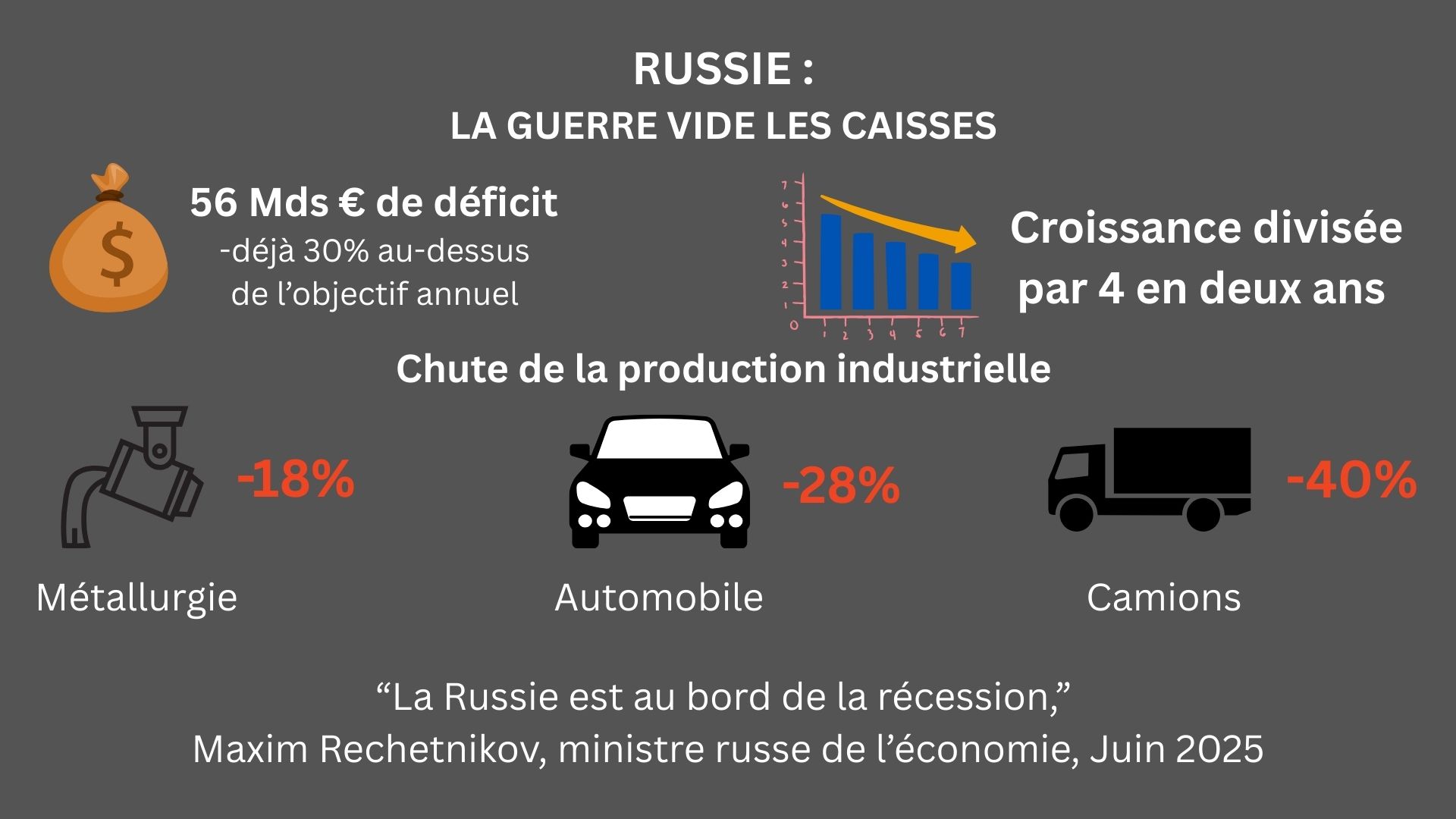

The result: by 2025, oil and gas revenues, which represent a third of the federal budget, have fallen by 18.5% in seven months. The budget deficit jumped to €56 billion at the end of July, a 30% increase over the annual target.

Forecasted growth is now only 0.9% (compared to 4% in 2023-2024) and reserve funds are almost exhausted. Industrial production is declining: metallurgy (-18%), automotive (-28% cars, -40% trucks), and coal (losses of over €3 billion).

Sanctions have cut off access to key equipment and components from Europe, the United States, and Japan. Lacking parts, many companies are resorting to “cannibalization”: dismantling several machines to rebuild a single one. In the automotive sector, KamAZ, Avtovaz, GAZ, and the Chelyabinsk and St. Petersburg tractor plants have reduced working hours to four days a week, with a 20% reduction in wages—a shortfall that is slowing consumption and weakening the economic fabric.

Hit by the loss of European markets and increased competition from Australia, Indonesia, and South Africa, the industry is seeing its production plummet and its debts mount. Even the largest producers are in the red, despite the shift toward Asia.

Corporate debt has nearly doubled since 2022, bad loans are exploding, and 48 of the 100 largest banks are in difficulty, including 15 loss-making banks in the first half of the year. The authorities recognize the risk of a systemic banking crisis.